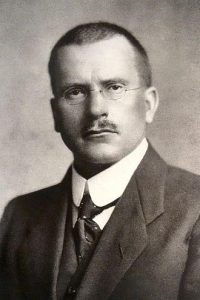

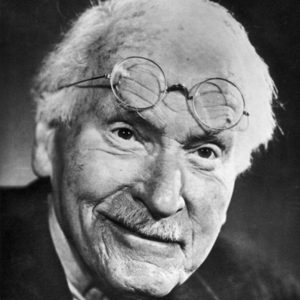

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist whose work quickly expanded to the English-speaking world in the early 20th Century. Jung learned much from Sigmund Freud, whose work on repression and resultant unconscious motivations of a ‘split’ psyche revolutionised psychological thinking, but ultimately Jung disagreed with Freud that neurosis was an illness born of infantile sexual repression.

For Jung, neurosis, or a feeling of being stuck, unhappy, alienated or enervated was best seen as a signpost for the way forward, not simply an indication of a trauma in the past.

Jung asks of the psychological symptom not so much: ‘Why? (i.e. What is the cause in the past?) but instead: ‘What for?’ (Where is it leading? What can I learn from it?)

Our dreams and fantasies, and how we express ourselves in writing, music,

dance, and image-making, are both personal to ourselves and yet connected to the universal nature of human symbol-making. For Jung, we are not mere animals driven by instinct with a thin veneer of civilisation to keep us in line with the laws of our social group. Instead, we have as well as our ‘base’ physical instincts also an in-born drive to find meaning and connection: to each other, to our shared human past, and to the natural world around us.

Individuation and the Collective Unconscious

Sustained engagement with the  symbolic level of our lived experience enables us to see archetypal patterns which recur in manifold forms across times and cultures. This is a paradox: we are both constrained by universal ‘archetypes’ or symbolic patterns as well as unique in our relationship to them. For Jung, our moral and ethical imperative is to come to terms with our ‘own myth’: this is the journey of ‘individuation’, or becoming the unique self in relation to other beings around us.

symbolic level of our lived experience enables us to see archetypal patterns which recur in manifold forms across times and cultures. This is a paradox: we are both constrained by universal ‘archetypes’ or symbolic patterns as well as unique in our relationship to them. For Jung, our moral and ethical imperative is to come to terms with our ‘own myth’: this is the journey of ‘individuation’, or becoming the unique self in relation to other beings around us.